By the early 1850’s, a line of established forts was too far removed to offer help to the settlers moving further west on the frontier, so a second cordon of forts was laid out to fill this advancing need. Fort Phantom Hill, along with three of its sister forts on the Texas Forts Trail (Ft. McKavett, Ft. Chadbourne, and Ft. Belknap), was established at this time. From its establishment in 1851 until recent times, Fort Phantom Hill has been on private property. Today, that property belongs to the Fort Phantom Foundation of Abilene, who, as a service to the heritage which the fort represents, has improved the site and made it available to the public.

By the early 1850’s, a line of established forts was too far removed to offer help to the settlers moving further west on the frontier, so a second cordon of forts was laid out to fill this advancing need. Fort Phantom Hill, along with three of its sister forts on the Texas Forts Trail (Ft. McKavett, Ft. Chadbourne, and Ft. Belknap), was established at this time. From its establishment in 1851 until recent times, Fort Phantom Hill has been on private property. Today, that property belongs to the Fort Phantom Foundation of Abilene, who, as a service to the heritage which the fort represents, has improved the site and made it available to the public.

At the fort site, three buildings and over a dozen chimneys remain of a complex which once housed five companies of infantry. While the ruins are sparse, the romance and nostalgia surrounding them make the trip well worth the short drive to see them. They are reached by driving north 14 miles from Interstate 20 at Abilene on FM 600, or by following the Texas Forts Trail route on FM 2833.

Captain Marcy Recommends a Route.

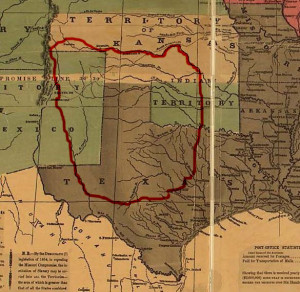

In 1849, Captain Randolph B. Marcy was sent to explore and mark the best route through the Comancheria, a wedge-shaped area with the base to the north and the point near Austin inhabited by the fierce Comanche Indians. This was intended to give safer passage for those Americans heading for the gold fields of California. As a result of Marcy’s recommendations from this expedition, the advanced line of forts including Fort Phantom Hill was established.

The Beauty of Phantom Hill

Lieutenant Colonel J.J. Abercrombie brought five companies of the Fifth Infantry to build “the Post on the Clear Fork of the Brazos,” arriving at the site on Friday, November 14, 1851. Abercrombie’s orders had come from General Persifor F. Smith who had just taken command of the North Texas frontier from ailing General William G. Belknap.

Belknap had been supervising construction of a post near the present city of Graham which was later to be named for him. His orders had been to build the second fort on Pecan Bayou in Coleman County. Smith, who was not knowledgeable of this area, changed these orders and directed the fort to be built on the Clear Fork of the Brazos in what is now Jones County.

This unreasoned alteration was to affect the future of the fort, for the lack of an adequate water supply and the scarcity of building timbers added greatly to the hardships of the men. This is reflected in the letters of Lt. Clinton W. Lear to his wife in Fort Washita:

Building Begins

In true military fashion the troops began work on the fort. A good stone quarry was located two miles south on the east bank of Elm Creek, and from this stone was built the structures which endure today. Military records indicate that in spite of the shortage of timber, the officers’ quarters and hospital were built of logs which had to be brought in by ox wagon from as far away as 40 miles. The company quarters and other buildings were of jacal construction, a building style consisting of vertical poles woven with brush and chinked with mud for walls and thatched roofs. Even these buildings were built with stone chimneys. Only the magazine, guardhouse, and permanent commissary storehouse were built entirely of stone.

Watercolor of Fort on Phantom Hill by Miller

Uniquely, this fort was never officially named; it was referred to as the “Post on the Clear Fork of the Brazos.” It came to be called Fort Phantom Hill for the hill on which it was located.

Romance and Legends

There are several romanticized, ghostly legends as to why it was named Phantom Hill; however, sources indicate that the name refers to the fact that from a distance, the hill rises sharply from the plains but levels out as it is approached, retreating like a phantom.

Life at the fort was difficult. Elm Creek was often dry, and the waters of the Clear Fork of the Brazos were brackish. At one point, an eighty-foot-deep walk-in well was dug, but its waters, too, proved unreliable. A historical irony exists in the fact that only two miles south of the fort today is a lake, named for the fort, which supplies the water for about 100,000 persons.

Native American Encounters

Soldiers at the fort had few encounters with Indians. It was an admitted tactical error to match infantry against the Comanches who were among the finest horsemen in the Americas. A band of Penateka Comanches led by the colorful Chief Buffalo Hump occasionally visited the fort as did groups of Lipans, Kiowas, and Kickapoos. The only threatened assault of any magnitude on Fort Phantom Hill is reported in an account by Mrs. Emma Johnson Elkins, who as a child lived at the fort with her parents:

Soldiers at the fort had few encounters with Indians. It was an admitted tactical error to match infantry against the Comanches who were among the finest horsemen in the Americas. A band of Penateka Comanches led by the colorful Chief Buffalo Hump occasionally visited the fort as did groups of Lipans, Kiowas, and Kickapoos. The only threatened assault of any magnitude on Fort Phantom Hill is reported in an account by Mrs. Emma Johnson Elkins, who as a child lived at the fort with her parents:

“A trench eight feet wide was cut around the garrison; the artillery was placed on a parapet in the center, ready to sweep the environments. A few days after completion of preparations, they were sighted, approaching. Their chief, Buffalo Hump, was in the lead, then his subordinates, warriors, squaws and papooses, 2,500 in all. Seeing the preparations, they passed on – with scowls and angry looks.”

Change of Command

Military records show that on April 27, 1852, Col. Ambercrombie turned command of the post over to Lt. Col. Carlos A. Waite, so he could return to England to claim title to a hereditary peerage. Waite was succeeded by Major H. H. Sibley on September 24, 1853. By this time, four of the five companies had been withdrawn, and the remaining company was reinforced by Company 1 of the 2nd Dragoons. First Lieutenant Newton C. Givens took command of the post on March 26, 1854 and was its commander at the time of its first abandonment on April 6, 1854.

The decline in rank of its commanders tells of the fort’s own decline in importance. Its many hardships combined with its poorly equipped troops made this initial occupation relatively uneventful; yet, at the time it was abandoned, the purpose of containing the Indian menace had been attained with the establishment of a reservation between the present towns of Albany and Throckmorton. Shortly after the troops left Phantom Hill, the fort mysteriously burned. The fire has been attributed to everyone from an irate officer’s wife to Indians, and later to federal sympathizers. No evidence substantiates any of these exits, so the fire shall forever remain as part of the fort’s mystery and romance.

From Fort to Way Station

In 1858, the remaining portions of the fort (primarily those buildings existing today) were utilized in establishing Way Station Number 54 by the Southern Overland Mail on the Butterfield Trail. The station was manned by Mr. and Mrs. Burlington who lived alone at the station. Mrs. Burlington prepared meals for the stage passengers.

In 1858, the remaining portions of the fort (primarily those buildings existing today) were utilized in establishing Way Station Number 54 by the Southern Overland Mail on the Butterfield Trail. The station was manned by Mr. and Mrs. Burlington who lived alone at the station. Mrs. Burlington prepared meals for the stage passengers.

One of the first stage passengers to make the trip to California, Warren Ormsby, wrote of the station, “Most of the chimneys are still standing and they reflected the light of the full moon as we drove up as might well become the title of Phantom Hill. There are ruins of from forty to fifty buildings. The magazine which stands today built entirely of stone is so little injured it is used for a company storehouse. The stable also is a fine stone building, so altogether, Phantom Hill is the cheapest and best new station on the route.”

During the Civil War, when the frontier was patrolled by Ranger companies and later the Frontier Battalion of the Confederacy, Colonel J.B. “Buck” Barry, or some of the units under his command, used Fort Phantom Hill as a base of field operations.

Beginning in 1871, the post served as a sub-post of Fort Griffin, near the present-day town of Albany. Captain Theodore Schwan led one prong of MacKenzie’s Raiders from the fort in the first series of Indian Wars from January to March 1872. It was during this time that the fort was visited by the famous Union General William T. Sherman as he inspected his Texas Department frontier.

Population 546

After the Indians on the frontier were under control, a town grew up around the ruins of the old fort. The 1880 census indicates it had 546 inhabitants. In 1876-77, it was a buying and shipping point for the great numbers of buffalo hides taken during the slaughter of the Southern Great Plains herds. The hopes of its citizens were spoiled when the temporary designation as county seat in May of 1881 was lost to the city of Anson in an election on November 14, 1881, and the Texas and Pacific Railroad routed its tracks many miles to the south. A letter written to the San Antonio Daily Express in 1892 said the town contained nothing but “one hotel, one saloon, one general store, one blacksmith shop and 10,000 prairie dogs.”

Fort Phantom Hill in the 21st Century

And so today, Fort Phantom Hill stands lonely and apart, aloof and dignified – a rock reminder of the colorful early days of Texas – a shrine on the rolling prairie.